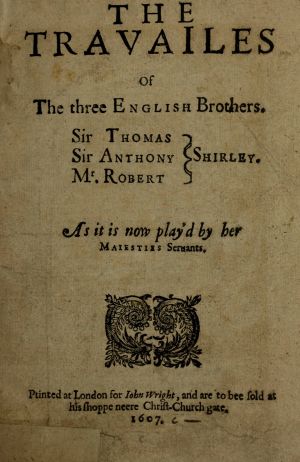

Travels of the Three English Brothers, The

Year (composition)

Written, performed and published in 1607 (Parr 7-9).

Year (first printed)

1607 (STC 6417)

Reprints (until 1700)

A second issue the same year (see below).

Authors (title-page ascription, including reprints)

John Day, William Rowley and George Wilkins (not on title page but in a dedicatory epistle found in some copies of the text; see below).

Authors proposed (attribution scholarship)

N/A

Genre

History (prologue); travel play (Parr); adventure play (Wiggins 5: 381)

Sources

- Anthony Nixon, The Three English Brothers (1607); probably read in manuscript before publication (Parr 7-8).

- William Parry, A New and Large Discourse of the Travels of Sir Anthony Sherley, Knight ... to the Persian Empire (1601) (Parr 84n).

Auspices

The title page reads, “As it is now play’d by her Maiesties Servants,” referring to Queen Anne’s Men. The Stationer’s Register describes it as “played at the Curten,” while an allusion in The Knight of the Burning Pestle refers to it as a Red Bull play (Jeffs xvii). The company played at both playhouses in 1607 (Parr 55n).

External Documentary Evidence

Payments

N/A

Stationers' Register

The Stationer’s Register entry for the quarto (29 June, 1607) does not name the authors.

Title-page ascription(s)

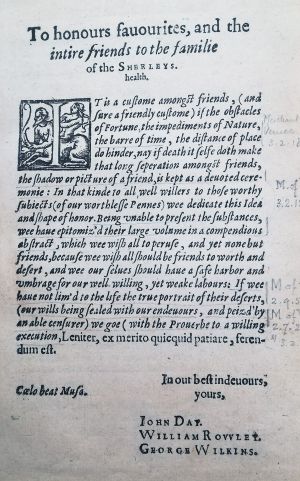

A second issue of the 1607 quarto adds an inserted page containing a dedicatory epistle signed by the authors, “Iohn Day. William Rowley. George Wilkins.” According to W.W. Greg, “the leaf appears to have been added after most of the copies were sold” and appears in the copies held by the British Library, the Dyce Collection (National Art Gallery, London), and the Folger Shakespeare Library (Greg, Bibliography, 1: 381).

In the epistle, the authors refer to themselves in the plural as “we” and to “our worthlesse Pennes.”

Biographical evidence (external)

Travels was written within the brief period of time (1606-8) in which George Wilkins attempted to make a living as a writer (Prior 137). Its subject matter accords with the “special interest in Mediterranean histories” that is apparent in all his work (Honigmann 196).

John Day spent much of his career writing collaborative plays, and this three-way partnership is thus no surprise (see Jeffs ix-xv). There is no other evidence of him writing with Rowley, but some scholars have argued that he had already collaborated with Wilkins on Law Tricks (Jeffs xv).

William Rowley’s name in the quarto text of Travels is the earliest historical record of his existence. An actor-playwright, it is possible, but not certain, that he was a player in Queen Anne’s Men when they performed Travels. The presence of a scene involving the famous clown Kempe is interesting, given Rowley’s specialization in clown acting (see Nicol, Middleton and Rowley 71-2). There are no further biographical connections between him and Day or Wilkins, but Wilkins’ prose work 'Three Miseries of Barbary is a source for a character’s name in Rowley’s The Thracian Wonder (Nicol, “Name”).

Theatrical provenance (external)

See ‘Auspices’ above.

The title page announces, “As it is now play’d by her Maiesties Servants”. Ernst Honigmann notes that it was rare for a play to be printed while it was still being performed onstage (188); the phrase “now play'd” is without parallel for “a new play between 1590 and 1616, the regular form being always in the past” (179). He finds it significant that the only exception is another Wilkins play, The Miseries of Enforced Marriage, performed by the King’s Men in the same year that it was published. Honigmann thus proposes that Wilkins had a habit of taking his plays to the press while they were still being performed, and without permission from the players (180).

Allusions

A joke in The Knight of the Burning Pestle alludes to Travels but makes no reference to its authorship (Jeffs xvii).

Print and MS attributions

None noted.

Internal Evidence

Explanation of terms

In the summaries below, it should be noted that almost all of the scholars cited (with the exception of Bullen and Golding) are analyzing Travels in order to determine whether George Wilkins contributed to Shakespeare’s Pericles. “Pericles 1-2” refers to the first two acts of that play, which are thought to contain most of Wilkins’ work; “Pericles 3-5” refers to the last three acts, which are thought to be primarily written by Shakespeare. “Travels W” refers to the scenes of the play that the scholars believe to be mostly by Wilkins; “Travels D&R” refers to the other scenes in the play, assumed to be by Day and/or Rowley (see ‘Critical Debate,’ below, for an explanation of how these sections were determined). Finally, Miseries refers to The Miseries of Enforced Marriage, the only known solo play by Wilkins.

Palaeographical evidence

N/A

Biographical evidence (internal)

None.

Theatrical provenance (internal)

None.

Metrical evidence

The earliest scholars of the play attributed authorship of individual scenes based on vague assessments of meter. According to A.H. Bullen, F.G. Fleay based his division of the play on Rowley’s “peculiar system of blank verse” and on Wilkins’ “short lines, especially 4-feet lines” (Bullen 19n1). Bullen himself referred to Rowley’s “grating metrical irregularities” in scene 7 (20). Robert Boyle similarly thought Rowley had a distinctively “uneven metre” but found no obvious metrical differences between Wilkins and Day (327).

In Defining Shakespeare (2003), MacDonald P. Jackson attempted a more rigorous analysis of Wilkins’ meter, using Ants Oras’ technique of comparing the pause patterns in Wilkins’ verse with that of Shakespeare (for Jackson’s description of Oras’s method, see 64-66, and for his own adaptation of it, see 86-7). Using the raw figures to create a “Pearson product moment correlation,” Jackson produced “a mathematical measure” of the relative differences. Ranking Shakespeare’s and Wilkins’ plays in terms of closeness to Pericles 3-5, he found Travels W to be 23rd out of 42 (89). Ranking them in terms of closeness to Pericles 1-2, he found Travels W at 15 out of 42. Wilkins’ section of Travels is thus somewhat closer to his section of Pericles than to Shakespeare’s; Jackson attributed the relatively undramatic difference (which contrasts with a more extreme result for Wilkins’ Miseries of Enforced Marriage) to Travels being a collaboration, and specifically to the influence of Day (88-90).

Using the same data, Jackson used a “chi-square statistic” to estimate “the probability that the two sets of figures could have been randomly drawn from the same parent population” (91). Comparing the Wilkins plays with six Shakespeare plays, he found Travels W and Miseries to be much less similar to Pericles 3-5 than the Shakespeare plays. However, although he didn’t say this, the data for his comparison of the plays with Pericles 1-2 shows Travels W to be very unlike it, whereas Miseries is very similar (93).

Evidence of rhymes

H. Dugdale Sykes was the first to note, in 1919, that Wilkins appears to have constantly used the same set of rhymes, which may indicate his presence (156-8).

In “Rhymes in Pericles” (1969), David J. Lake explored Wilkins’ rhyming more systematically. He noted the assonantal nature of some of the rhymes in Pericles (such as sung/come in the first two lines), which are rare in Shakespeare and argued that they cannot be explained as deliberate archaisms because numerous examples are found in Travels and The Miseries of Enforced Marriage (139-40). Finding such rhymes also to be rare in Day and infrequent in Rowley, Lake determined Wilkins to be the culprit, and noted that all but one of the examples in Travels fall within the scenes traditionally associated with Wilkins (141-2).

Lake also explored more thoroughly Sykes’s reference to Wilkins’ tendency to “mingle” rhyming and blank verse. He noted that Wilkins tended to include rhymes in the middle of a blank verse or even prose speech, rather than putting them at the end, and that he also often put unrhyming lines in the middle of a rhymed speech (142; Lake called the latter lines ‘rifts’). Lake also noted ‘rafts’ (rhymed sections preceded and followed by blank verse), finding 25 in the Wilkins scenes; there were only 7 elsewhere, all of which he attributed to Rowley, who was “as careless in this matter as Wilkins” (142).

In Defining Shakespeare (2003), Jackson cited Lake’s study of rhymes approvingly, then presented his own study of whether rhymes in Miseries are repeated in other plays, including Travels W (his methodology is explained at 97-102). He came up with a table ranking the percentages of rhymes that the plays share with Miseries. Pericles 1-2 comes first with 40% and Travels W is next with 26.7%. After that comes Measure for Measure, with 23.9%. Jackson thus concluded that the first two plays are much more ‘Wilkinsian’ in their rhymes (102).

In two Notes and Queries articles in the 2010s, John Klause claimed that there are logical flaws in Jackson’s counting of rhymes and argued that the distinctions among the plays are not as clear as he had made them look (“Rhyme”, “Controversy”). Jackson rejected Klause’s arguments (“Reasoning”, “Rhymes”). Travels is mentioned only briefly in this debate and nothing new is said about it.

Chronological evidence

N/A

Vocabulary

In 1969, David J. Lake argued that Wilkins’ work contains an unusual preponderance of the of the words yon (and related words) and sin, with a frequency much higher than that in Shakespeare, Day or Rowley. In Travels, he noted that yon and related words appear only in the scenes attributed to Wilkins (“Wilkins” 289-90). He also noted that every instance of sin in the Wilkins scenes is “uncalled for by the context,” which he regarded as evidence for it being “a favourite word” in contrast to the unremarkable instances in the works for Rowley and Day (“Wilkins” 291).

Oaths and interjections

None noted.

Linguistic evidence

H. Dugdale Sykes’s Sidelights on Shakespeare (1929) paid close attention to Wilkins’ quirky grammatical constructions, including some examples from Travels (152, 154-55, 157, 158, 162-3, 170-71, 172, 187, 188n1, 195). He concluded that Wilkins's writing is marked by three oddities:

- “Frequent omission of the relative pronoun in the nominative case” (150), although he notes only one example in Travels (152)

- Verbal antitheses, which “run riot” through his share of Travels (152)

- “Repeating a word within the line,” which he does “two or three times” in Travels (155).

In 1990, MacDonald P. Jackson elaborated on a point briefly made by E.A.J. Honigmann (194) about Wilkins’ unusual uses of the word which. He defined three especially important unusual forms:

- which meaning ‘and this’ and qualifying a noun that immediately follows

- which preceded by the definite article

- which beginning a speech that is not a question (“Pericles” 193)

In Travels, he found that “the three-fifths of the play that Lake follows Sykes in ascribing to Wilkins” contains an amount “well below that for acts I and II of Pericles, but much closer to theirs than is the work of other dramatists” while the parts allocated to Day and Rowley contain just one (196). The argument is strengthened by his inclusion of other plays by Day and Rowley in the tests. Jackson reiterates these findings in Defining Shakespeare (128).

In a 1993 article, Jackson proposed that the frequent presence of infinitive forms of verbs can be an indicator of Wilkins. The “rate of infinitives per 1000 words” compared to Shakespeare and to selected Day and Rowley plays, turned out to be “anomalously high” in Pericles 1-2, and in Wilkins’ other plays (“Authorship” 198). In regard to Travels, Jackson showed that the rate in the purported Wilkins section was higher than that in the share apportioned to Day and Rowley (199). He also tested the general frequency of the word to in selected plays and found that “Wilkins is the most prominent presence” among the plays with the highest frequencies, including his section of Travels, although he acknowledged that Heywood and Massinger scored highly too (200). Overall, Jackson concludes that this is further supporting evidence for Wilkins.

In Defining Shakespeare (2003), Jackson enhanced this study of infinitives. Comparing the rate of infinitives in the W section of Travels compared to the D&R section, he finds it at 17.5/1000 words compared to 9.7, and considers the probability of this being chance as “less than a thousand” (120-22n67). And returning to the amount of the word to, he found both of two samples from Travels W appearing in the top 10 of plays (122-23).

Defining Shakespeare includes the results of many studies by Jackson of Pericles that support Wilkins’ authorship of scenes attributed to him in Travels:

- He studied Wilkins’ habit of treating “combinations of personal pronouns followed by are or have” as monosyllabic rather than disyllabic; he found after a “quick count” that the ratio in Travels W is congruent with Pericles 1-2 (95).

- In an expansive study of function words, he counted occurrences of the words a, and, but, by, for, from, in it, of, that, the, to, and with using “eighty-six samples from plays by known dramatists” collected for his 1979 study of Middleton’s collaborations (113). He supplemented these with “a third and fourth sample from” Miseries, “two samples from Wilkins’ share of” Travels, “one sample from the portion of The Travels generally attributed to Wilkins’ collaborators” and “one sample from that portion of William Rowley’s A Woman Never Vexed which David Lake tentatively assigned to Wilkins, namely the last two acts” (115; for an explanation of the situation with this play, see ‘Critical Commentary’ below). Each sample consisted of “one thousand consecutive instances of the thirteen selected function words” except for Travels D&R, where “there was not quite enough text to provide a sample of the standard size” (115). In the end, Jackson had created 112 samples, including seven from Wilkins and nine from Shakespeare. He then calculated the “chi-square fit” of each sample with each of the two sections of Pericles to assess their similarities (116). When they were compared with Pericles' 3-5, Travels D&R was number 7 out of 112 (Jackson didn’t say where the Wilkins samples appeared). When compared with Pericles 1-2, Miseries came first in terms of closeness, and the two samples of Travels W came third and fifth respectively, indicating a strong connection between these texts (no Shakespeare plays appear in the top 10); Travels D&R is at #59, suggesting it to be very different (Table 14, p. 117).

- He studied the ratio of most to unto, another indicator of Wilkins writing Pericles 1-2, as Wilkins tended to use unto more often than most; this is true of Travels W too (137). Jackson studied the ratio in three plays each by Day and Rowley and found Rowley using most rather more than Day did; although the numbers are small, he claimed that “such as they are, they reflect accurately the slight difference between Day’s and Rowley’s practices.”

- Considering the linguistic markers such as those studied by Cyrus Hoy, David Lake and himself in their studies of the Fletcher and Middleton canons, Jackson found the Wilkins canon unconducive to such studies, given its small number of texts (139). However, discussing the use of ye (as opposed to you), he noted that in their non-collaborative plays, “neither Day nor Wilkins made very much use of ye, whereas Rowley, whose plays vary in his treatment of the pronoun, used it 34 times in A Shoemaker a Gentleman (1608), the Rowley play that is easily the nearest to Travels in its date of composition” and he thus noted that “it appears significant that occurrences of ye cluster within scenes” attributed to Rowley; 16 of the 25 examples occur there, even though he only wrote about quarter of the play (139).

- He studied has/hath and does/doth ratios, finding Travels W to reflect Wilkins’ greater tendency toward hath and doth (140). He also found commonalities between Travels W and the other Wilkins-related texts in the rareness of contractions using th’ and the use of ’t, h’as and him’s (141).

Stage directions

None noted.

Verbal parallels

Although he was not systematic in proving it, Robert Boyle was the first to argue that Wilkins was a habitual repeater of phrases and that these “Wilkinsisms” can help to identify him. He provided a list of parallel passages between Pericles, Travels, and Miseries (327-9).

S.R. Golding was one of the few scholars to be interested in Day’s contribution; he proposed some verbal parallels with his other plays (418-20).

In Defining Shakespeare, Jackson notes some parallel passages in which the same distinctive uses of words appear in both Pericles and Travels (145-7).

Image clusters

None noted.

Critical Debate

There is no doubt as to the identities of the authors of Travels, but there has been debate and discussion over how they divided their work. Overall, attribution studies appear at first glance to have arrived at a consensus, but the contributions of Day and Rowley are in fact less clear than those of Wilkins. This is because most studies have been undertaken with a view toward determining Wilkins’ share in Pericles; they thus treat Travels as a side-project and are less interested in distinguishing Day and Rowley from one another.

The overall story of approaches to Travels is as follows. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, several scholars attempted to ascertain who wrote which scene, ranging from brief and impressionistic comments to a very detailed study by H. Dugdale Sykes conducted as part of his study of Pericles. A vague consensus emerged, at least about Wilkins’ contributions. In the 1960s, David J. Lake, focusing on Pericles, brought a more rigorous methodology, using various approaches to linguistic and rhyming eccentricities. His assumptions about Travels were based on the apparent existing consensus. MacDonald P. Jackson conducted further studies as part of his work on Pericles in the 1990s and 2000s. While the case for Wilkins’ authorship of Pericles is now extremely clear and convincing, Travels still awaits a modern scholar who will pay attention to it for its own sake and look more closely at the other authors.

It is helpful here to summarize the approximate consensus that emerged from the earliest studies of the play. What follows is a scene-by-scene breakdown with comments on the claims for authorship made in the earliest studies. I have highlighted the proposed authors to enable a quick visual impression of which scenes produced consistent attributions and which did not. The sources are as follows:

- F.G. Fleay studied the authorship of Travels in the 1870s, presumably during the creation of his 1874 study of Pericles. A.H. Bullen (see below) quoted Fleay’s conclusions, which had partially influenced his own (19-20). I have not identified a published source for these quotations; perhaps Bullen was quoting a private letter. Fleay would later publish a slightly different breakdown of the scenes in 1891 (see below), but I have included both versions as the first was an influence on Bullen and Boyle.

- A.H. Bullen’s brief thoughts in his edition of The Works of John Day (1881) are a vague, incomplete, and impressionistic survey, but deserve note as the first published study. Bullen was responding to the ideas of Fleay (see above).

- Robert Boyle’s study of Wilkins and Pericles (1885) was also responding to Fleay as quoted by Bullen (see above).

- F.G. Fleay finally published his breakdown of the play’s authorship in his Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama (1891). It referred to metrical analysis but offered no data. It contained two differences from what he had communicated to Bullen in the 1870s (see above): Fleay appears to have changed his mind about the authorship of scenes 12 and 13.

- H. Dugdayle Sykes, in Sidelights in Shakespeare (1919), studied a variety of evidence including verbal parallels.

- S.R. Golding’s study of “Day and Wilkins as Collaborators” (1926) is also centered on verbal parallels.

- Dewar M. Robb’s study of the Rowley canon (1950) lacks supporting evidence for its conclusions, but is worth noting as a rare example of a study by a Rowley scholar.

In what follows, I have also attempted to clarify the confusing matter of scene divisions. Q is not divided into scenes; Parr’s edition is the first to do so. Unless there is evidence otherwise, I assume the scholars’ scene divisions to be the same as Parr’s (which seem to me logical); Boyle (326), Sykes (145n1) and Robb (135), however, divide the play according to a slightly different model (to my mind, incorrectly). Line references are to Parr.

- Prologue. Few scholars have addressed the authorship of the Prologue. Fleay and Golding attributed it to Rowley; no other study directly attributes an author to it.

- Scene 1. Anthony and Robert Sherley impress the Sophy of Persia and incur the jealousy of Halibeck and Calimath. Bullen thought the author was Rowley, being typically at “too high a key”, lacking “naturalness and freedom” and having a style “forced without being dignified” (20). Fleay, Boyle and Golding also attributed it to Rowley.

- Scene 2. Anthony and Robert help the Sophy defeat the Turks; the Sophy sends Anthony and Halibeck to forge an alliance with the Christian world against them. Bullen thought it Wilkins at first, but Rowley from 89 onward, especially the “savagely eloquent” 128-33 (20). However, Fleay, Boyle, Sykes and Golding attributed the entire scene to Wilkins.

- Scene 3. The Sophy's Niece falls in love with Robert; in this comic scene, the Niece and her maid frequently speak in prose. Bullen saw Day in the “playful naughtiness” of the conversation between the Sophy’s Niece and Dalibra (19). Fleay, Boyle and Golding also attributed it to Day.

- Scene 4. A short scene (49 lines), beginning with a speech by the Chorus; Anthony arrives in Russia but is arrested when Halibeck spreads rumours of his low birth. Fleay cautiously attributed it to Day. Boyle thought it was Day or Rowley. But Sykes and Golding attributed it to Wilkins.

- Scene 5. The Chorus explains how Anthony was released after the rumour was quashed; he is welcomed to Rome. Fleay cautiously attributed it to Day. Boyle was certain only that it wasn’t Wilkins. But Sykes and Golding attributed it to Wilkins.

- Scene 6. The Chorus describes Thomas's voyage to see his brothers; Thomas lands on a Greek island and is captured by Turks. Fleay, Boyle, Sykes and Golding attributed it to Wilkins. Boyle proposed that the Chorus could be Rowley, as its geographical confusions would not have been made by Day or Wilkins (328); however, the Chorus is in fact following the source material (see Parr, n. to 6.16).

- Scene 7. Robert captures Turkish prisoners in battle; one of them is a Christian who gives him a message from Thomas, imprisoned in Constantinople. Fleay, Boyle and Golding attributed this scene to Rowley.

- Scene 8. The Great Turk refuses Robert's offer of a prisoner swap, after realizing Thomas’s importance. Fleay, Boyle, Golding and Sykes attributed it to Wilkins.

- Scene 9. Anthony is in Venice and needs to repay a debt to Zariph the Jew; he also watches the English actor Will Kemp engage in comic repartee with commedia dell'arte actors; this section is mostly prose. Bullen saw Rowley’s “grossness” in the Kemp scene, but also Day in the “quickness and pertness of the sallies” (19). He could not accept that Day created Zariph the Jew (19n1), attributing him to Rowley because he is “very life-like” but drawn with a “few rough strokes” rather than as a “finished sketch” (19-20). However, Fleay, Boyle and Golding attributed the entire scene to Day (note that Boyle treats 9 and 10 as one scene, which he calls “9”).

- Scene 10. Halibeck has intercepted money sent by the Sophy to Anthony and plots with Zariph to deny it to him; Anthony is then arrested by Zariph at a banquet. Fleay and Golding attributed it to Rowley. Boyle attributed it to Day (note that Boyle treats 9 and 10 as one scene, which he calls “9”).

- Scene 11. The Sophy discovers that his Niece loves Robert and fakes his execution before allowing them to marry. Bullen attributed to Day the Niece’s “spirited” avowal of love for Robert and defiance of his accusers, claiming that his heroines have a “charming frankness of manner” and “know how to express their likes and dislikes gracefully and vigorously” (19). Fleay also attributed it to Day. However, Boyle and Sykes attributed it to Wilkins (note that they call this scene “10”; Boyle also states incorrectly that Fleay attributed it to Rowley). Golding, unusually, considers it to be by both Day and Wilkins in collaboration.

- Scene 12. Thomas is tortured by the Great Turk but is saved when an English agent requests his freedom. Bullen attributed it to Day, as did Fleay in his 1870s study; however, by 1891, Fleay had attributed it to Wilkins. Some critics divide the scene in two, viz:

- 12.1-57. Boyle called this section “scene 11” and regarded it as Day, but thought the Jailer’s opening prose speech (1-16) might be Wilkins. Golding attributed it to Day.

- 12.58-155. Boyle, Sykes and Golding attributed this to Wilkins (note that Boyle and Sykes called this section “scene 12”).

- Scene 13. Robert has a child with the Niece and discusses its baptism with a Hermit; Halibeck tells the Sophy that Anthony's mission was a failure but Robert proves Halibeck the cause and has him executed; the Sophy permits Robert to baptize his child and build a church in Persia. Bullen attributed it to Wilkins, as it is “carefully and equably written” (20). However, most scholars have considered this scene to have divided authorship, viz:

- 13.1-175. Fleay attributed this to Day in his 1870s study. However, in his 1891 publication he attributed it to Wilkins, as did Boyle, Sykes (implicitly) and Golding.

- 13.176-202. In the last few lines of the scene, the Sophy agrees to let Robert build a church and a Christian school in Persia. Fleay, Boyle and Golding attributed these lines to Rowley.

- Epilogue. The Chorus reports on the fates of the other two brothers. Fleay in the 1870s and Bullen attributed it to Rowley (20), but no other study directly attributes an author to it.

It will be seen from this list that there is a fairly strong consensus, but not for all scenes. The major disagreements are over scenes 4 and 5, 10, and 11, and they have not been fully addressed in subsequent scholarship. Most studies have not directly addressed the authorship of the prologue or epilogue.

Overall, Sykes was the most influential upon subsequent scholarship. F.D. Hoeniger cited him approvingly in the 1963 Arden Pericles (lx-xi); so too did Brian Vickers in his detailed survey of the Pericles studies (297-306), although he cautioned that Sykes’ methodology was not always systematic or entirely accurate (297, 302).

Sykes’ influence became very important when David J. Lake returned to Travels for a series of articles investigating Pericles. Lake followed Sykes’ conclusions about Wilkins’ presence in that play (142) and labelled his attributed scenes “Travels W,” treating them as a consistent text against which theories could be tested. Jackson used the same approach in his studies of Pericles in the 1990s and 2000s, sometimes also combining together the rest of the scenes as “Travels D&R.”

More work needs to be done on Day and Rowley’s contributions. But this does not diminish the very compelling work that scholars have done on Wilkins. Jackson summarises by saying that if one simply counts instances of three pieces of evidence mentioned above: the uses of ‘which’, the elisions of the relative pronoun, and the assonantal near-rhymes, one can see an enormous difference between Travels W, Miseries and Pericles 1-2 on the one hand, and Travels D&R and Pericles 3-5 on the other: the former group contains an enormously higher number of these features than the other group (Defining 160-1). Overall, Jackson concludes that all the evidence combines “to form a style that appears in Pericles 1-2, The Miseries of Enforced Marriage, Wilkins’s share of The Travels of the Three English Brothers, and nowhere else in English Renaissance drama” (169).

Critical Commentary

The relative lack of interest in Rowley has resulted in some confusion that might complicate the findings of these studies. In “The ‘Pericles’ Candidates,” Lake studied Rowley’s A New Wonder, a Woman Never Vexed, a play often noted to have a marked change of style in its last two acts. He observed that the style seemed familiar: whoever wrote those two acts could also have written the ‘Wilkins’ section of Travels. Lake resolved this problem by proposing that Wilkins did indeed write Acts 4 and 5 of New Wonder (140-1). However, in Defining Shakespeare, Jackson was inconsistent in his treatment of New Wonder: in a footnote, he refused to go so far as to accept it into the Wilkins canon (as Acts 4-5 contain some of his characteristics but not others), but he admitted that the possibility “needs further investigation” (115n59). Yet in his study of function words, he found New Wonder 4-5 ranked 8th out of 112 plays in terms of closeness to Pericles 1-2, leading him to suggest that Lake may have been correct about its authorship (116). However, later in the same book, he treats the play unproblematically as Rowley’s (137). It seems clear that any study of Wilkins needs to look more closely at A New Wonder, in case it may represent a second example of a collaboration between Rowley and Wilkins.

Further Thoughts

One intriguing parallel has gone overlooked. The epistle by the authors includes the line “to all well-willers to those worthy subjects of our worthless pens.” This is echoed in the dedicatory epistle to Middleton and Rowley’s A Fair Quarrel (1616), signed by Rowley, which says of the dedicatee, “his poor well-willer wishes his best wishes” (3); there is also a similarity with the epistle to the reader in Middleton and Rowley’s The World Tossed at Tennis (1620), again written by Rowley, which begins “To the well-wishing, well-reading understander.” If Rowley wrote the epistle to Travels, this might suggest that he had a more important role in its writing and publication than has been considered.

Also of note is that the scholarly consensus gives Rowley the beginning and end of the play, something often seen in his later collaborations with Middleton (Mooney; Nicol, Middleton and Rowley 26-32).

Works Cited

Boyle, Robert. “On Wilkins’ Share in the Play Called Shakspere’s Pericles.” New Shakspere Society’s Transactions 8, 1886, pp. 323–40.

Bullen, A. H., editor. The Works of John Day, Now First Collected, with an Introduction and Notes. Chiswick Press, 1881.

Fleay, F.G. “On the Play of Pericles.” New Shakspere Society’s Transactions, vol. 1, 1874, pp. 195–209.

———. A Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama. Reeves and Turner, 1891.

Golding, S. R. “Day and Wilkins as Collaborators.” Notes and Queries, vol. 150, no. 24, 1926, pp. 417–21 and vol. 150, no. 25, 1926, pp. 436–38.

Hoeniger, F. D., editor. Pericles. Methuen, 1963.

Honigmann, E. A. J. The Stability of Shakespeare’s Text. Edward Arnold, 1965.

Hoy, Cyrus. “The Shares of Fletcher and his Collaborators in the Beaumont and Fletcher Canon (I).” Studies in Bibliography 8, 1956, pp. 129-46.

Jackson, MacDonald P. “The Authorship of Pericles: The Evidence of Infinitives.” Notes and Queries, vol. 40, no. 2, 1993, pp. 197–200.

———. Defining Shakespeare: Pericles as Test Case. Oxford University Press, 2003.

———. “Pericles, Acts I and II: New Evidence for George Wilkins.” Notes and Queries, vol. 37, no. 2, 1990, pp. 192–96.

———. “Reasoning about Rhyme: George Wilkins and Pericles.” Notes and Queries, vol. 60, no. 3, 2013, pp. 434–38.

———. “Rhymes and Authors: Shakespeare, Wilkins, and Pericles.” Notes and Queries, vol. 58, no. 2, 2011, pp. 260–66.

———. Studies in Attribution: Middleton and Shakespeare. Universität Salzburg, 1979.

Jeffs, Robin, editor. The Works of John Day, Reprinted from the Collected Edition by A.H. Bullen (1881). Holland Press, 1963.

Klause, John. “A Controversy over Rhyme and Authorship in Pericles.” Notes and Queries, vol. 59, no. 4, 2012, pp. 538–44.

———. “Rhyme and the Authorship of Pericles.” Notes and Queries, vol. 57, no. 3, 2010, pp. 395–400.

Lake, David J. The Canon of Thomas Middleton’s Plays. Cambridge University Press, 1975.

———. “The ‘Pericles’ Candidates - Heywood, Rowley, Wilkins.” Notes and Queries, vol. 17, no. 4, 1970, pp. 135–41.

———. “Rhymes in ‘Pericles.’” Notes and Queries, vol. 16, no. 4, 1969, pp. 139–43.

———. “Wilkins and ‘Pericles’ - Vocabulary (I).” Notes and Queries, vol. 16, no. 8, 1969, pp. 288–91.

Mooney, Michael E. “‘Framing’ as Collaborative Technique: Two Middleton-Rowley Plays.” Comparative Drama vol. 13 (1979), pp. 127-41.

Nicol, David. Middleton and Rowley: Forms of Collaboration in the Jacobean Playhouse. University of Toronto Press, 2012.

———. “The Name ‘Lillia Guida’ in William Rowley’s The Thracian Wonder.” Notes and Queries vol. 50, 2003, pp. 441-43.

Parr, Anthony, editor. Three Renaissance Travel Plays. Manchester University Press, 1995.

Prior, Roger. “The Life of George Wilkins.” Shakespeare Survey, vol. 25, 1972, pp. 137–52.

Robb, Dewar M. “The Canon of William Rowley’s Plays.” Modern Language Review 45, 1990, pp. 129-41.

Sykes, H. Dugdale. Sidelights on Shakespeare. Shakespeare Head, 1919.

Vickers, Brian. Shakespeare, Co-Author: A Historical Study of Five Collaborative Plays. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Page created and maintained by David Nicol; updated on 26 June 2023.