Difference between revisions of "Bloody Banquet, The"

m |

m (→Works Cited) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

Interestingly, in 1640 two playwrights associated with Beeston, Richard Brome and Thomas Nabbes, separately complained about the abridgement of their texts for performance (Bentley 1971: 236-7). This indicates an apparent preference for shorter plays on the part of Beeston, and Beeston’s willingness to commission cuts to pre-existing texts might explain further why the surviving version of ''The Bloody Banquet'' is shorter than any other play by Dekker or Middleton (except, in Middleton’s case, ''The Nice Valour'' (1622), although this work was published more than two decades after its original performances, and is itself likely a text that has undergone adaptation). | Interestingly, in 1640 two playwrights associated with Beeston, Richard Brome and Thomas Nabbes, separately complained about the abridgement of their texts for performance (Bentley 1971: 236-7). This indicates an apparent preference for shorter plays on the part of Beeston, and Beeston’s willingness to commission cuts to pre-existing texts might explain further why the surviving version of ''The Bloody Banquet'' is shorter than any other play by Dekker or Middleton (except, in Middleton’s case, ''The Nice Valour'' (1622), although this work was published more than two decades after its original performances, and is itself likely a text that has undergone adaptation). | ||

It is worth noting here that the quarto text’s use of act/scene divisions that are clumsily imposed upon the text after 5.1.110 (creating a false scene break into 5.1 and a non-existent ‘5.2’; see below) suggests that the copy of the play that lies behind the quarto may have had its act/scene divisions imposed onto it sometime after its original performance. Indeed, if the play was originally performed at an outdoor theatre (like the Red Bull) it would not have used act divisions (see Taylor 1993), but these would have been added into the play when it transferred to an indoor theatre (the Cockpit). The problematic split in the middle of 5.1 could be evidence of later act/scene divisions added into the text as part of a textual restructuring undertaken following the larger process of adaptation. Claire Kimball and Charlene V. Smith have pointed out that the encounter between Tymethes and the Young Queen in 4.3 benefits from the application of pitch darkness that would have been made possible by performance in an indoor playhouse (Kimball and Smith 2024: | It is worth noting here that the quarto text’s use of act/scene divisions that are clumsily imposed upon the text after 5.1.110 (creating a false scene break into 5.1 and a non-existent ‘5.2’; see below) suggests that the copy of the play that lies behind the quarto may have had its act/scene divisions imposed onto it sometime after its original performance. Indeed, if the play was originally performed at an outdoor theatre (like the Red Bull) it would not have used act divisions (see Taylor 1993), but these would have been added into the play when it transferred to an indoor theatre (the Cockpit). The problematic split in the middle of 5.1 could be evidence of later act/scene divisions added into the text as part of a textual restructuring undertaken following the larger process of adaptation. Claire Kimball and Charlene V. Smith have pointed out that the encounter between Tymethes and the Young Queen in 4.3 benefits from the application of pitch darkness that would have been made possible by performance in an indoor playhouse (Kimball and Smith 2024: 177-8), in similar vein to a ‘dark scene’ in Webster’s Blackfriars play ''The Duchess of Malfi'' (1614); if so, it might indicate that something in the dramaturgy of this scene might also have been altered by the play’s adapter, if the play were transported from an outdoor playhouse to the indoor Cockpit. | ||

=== Metrical evidence === | === Metrical evidence === | ||

| Line 231: | Line 231: | ||

Gaines, Barry, and Grace Ioppolo, eds (2023), ''The Collected Works of Thomas Heywood'', vol. iii (Oxford: Oxford University Press). | Gaines, Barry, and Grace Ioppolo, eds (2023), ''The Collected Works of Thomas Heywood'', vol. iii (Oxford: Oxford University Press). | ||

Greatley-Hirsch, Brett, Matteo Pangallo, and Rachel White (2024), ‘“Text up his name”: The Authorship of the Manuscript Play ''Dick of | Greatley-Hirsch, Brett, Matteo Pangallo, and Rachel White (2024), ‘“Text up his name”: The Authorship of the Manuscript Play ''Dick of Devonshire''’, ''Studies in Philology'' (121), 163-87. | ||

Green, William David (2020), ‘“Such Violent Hands”: The Theme of Cannibalism and the Implications of Authorship in the 1623 Text of ''Titus Andronicus''’, ''Exchanges'' (7), 182–99. | Green, William David (2020), ‘“Such Violent Hands”: The Theme of Cannibalism and the Implications of Authorship in the 1623 Text of ''Titus Andronicus''’, ''Exchanges'' (7), 182–99. | ||

| Line 241: | Line 241: | ||

Jackson, MacDonald P. (1979), ''Studies in Attribution: Middleton and Shakespeare'' (Salzburg: Universität Salzberg. | Jackson, MacDonald P. (1979), ''Studies in Attribution: Middleton and Shakespeare'' (Salzburg: Universität Salzberg. | ||

Kimball, Claire, and Charlene V. Smith (2024), ‘''The Bloody Banquet'' in Performance’, in William David Green, Anna L. Hegland, and Sam Jermy, eds, ''The Theatrical Legacy of Thomas Middleton, 1624–2024'' (London: Routledge) | Kimball, Claire, and Charlene V. Smith (2024), ‘''The Bloody Banquet'' in Performance’, in William David Green, Anna L. Hegland, and Sam Jermy, eds, ''The Theatrical Legacy of Thomas Middleton, 1624–2024'' (London: Routledge), 169-84. | ||

Lake, David J. (1975), ''The Canon of Thomas Middleton’s Plays: Internal Evidence for the Major Problems of Authorship'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). | Lake, David J. (1975), ''The Canon of Thomas Middleton’s Plays: Internal Evidence for the Major Problems of Authorship'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). | ||

Latest revision as of 14:45, 5 March 2024

Year (composition)[edit | edit source]

The date of composition remains uncertain, but probably falls within the range 1608-10.

In Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino’s companion to the 2007 Collected Works of Middleton (colloquially known as The Oxford Middleton), a date of 1608–9 is given (2007a: 364). Stylistic evidence is offered showing that versification and verbal parallels in the shares of both authors indicate a date of composition at the end of the first decade of the seventeenth century. As pointed out elsewhere by Taylor, whereas Dekker’s rate of rhymed lines as proportionate to lines of verse follows no clear pattern, Middleton’s rate began clearly dropping after the composition of A Mad World, My Masters in 1605: the rate in the Middleton scenes of The Bloody Banquet (21%) places that play within Middleton’s 1605–11 range (2001: 4–5). Their other evidence for dating is also taken from Taylor’s analysis, specifically: references to court drunkenness (2.1.37–41), which would have been particularly topical in light of the Jacobean court’s reputation for drunkenness, particularly after 1606 (2001: 8); references to a dearth in harvests (2.1.43–6; 2.2.2–10), which would be topical in 1608-9 due to the high corn prices of those years leading to rioting in England (2001: 8–9); and an apparent reference to pirates (2.1.70–3), which would have been particularly topical from 1609 onward, following King James I’s ‘Proclamation against Pirats’ of 8 January 1609 (2001: 10). From this convergence of evidence, 1608-9 arises as the most plausible date range for the Oxford Middleton editors.

In his entry for The Bloody Banquet in British Drama, 1533-1642: A Catalogue (#1624), Martin Wiggins (in association with Catherine Richardson) pushes this slightly later, to 1610, observing that 1608–9 is ‘inherently less plausible owing to theatre closures in those years’. Wiggins notes that the reference to Lapyrus as the ‘devil in the vault’ (2.2.36) associates him with a description often applied to Guy Fawkes, suggesting that the play must at the very least post-date the foiling of the Gunpowder Plot in November 1605, but he also points out that there were a cluster of such allusions in 1610-11, including, perhaps most relevantly, in Thomas Dekker and Thomas Middleton’s The Roaring Girl (1611) and Dekker’s If This Be Not a Good Play, The Devil Is In It (1611).

Although Dekkerian/Middletonian recollections of the Gunpowder Plot in 1610-11 do not preclude the authors from also having had such an interest in 1608-9, the fact that the theatres were closed due to plague for the entirety of 1609 (Barroll 1991: 173, 178–86) does significantly reduce the likelihood of that being The Bloody Banquet’s year of first performance. Additionally, in 1608 the theatres were open between April and June, but (aside from part of July) were closed for the rest of that year (Barroll 1991: 173); apart from the reference to Jacobean courtly drunkenness, April-July 1608 seems slightly too early for the strongest topical allusions identified above to receive a particularly powerful audience reaction (as the public response to corn prices was only just beginning, and James’s ‘Proclamation against Pirats’ did not come about until the start of 1609). Consequently, Wiggins’s suggestion of a 1610 date does seem persuasive.

However, Wiggins’s protestations regarding the 1608–9 theatre closures are only relevant in terms of performance, not composition. With the theatres closed, it seems unlikely that Middleton and Dekker simply ceased writing, as they had to be ready for when the theatres were able to reopen.

Interestingly, Dekker took a noticeable interest in the corn protests of 1609, as shown through his prose pamphlet Work for Armourers, published in that year. Dekker takes aim at the ‘rich Farmers, Land-lords, and Graziers’ who ‘transport your corne, butter, cheese and all needfull commoditiess into other countries, of purpose to famish and impouerish these hated whining wretches’ by causing corn prices to increase ‘from foure to ten shillings a bushell,’ and then again ‘from ten to twelue shillings’ (F2v). As Taylor notes, the reference in The Bloody Banquet to ‘an angel a bushel’ (2.1.44–5) reflects Dekker’s protests about bushels increasing ‘from ten to twelue shillings’ in Work for Armourors; an angel was a gold coin equalling eleven shillings (2001: 9). The Bloody Banquet might therefore also reflect Dekker’s concern with corn prices in 1609.

As such, due to Dekker’s interest in the corn protests of this year, combined with the play’s reference to pirating, 1609 seems a good ‘best guess’ for composition of The Bloody Banquet, even if first performance may have had to have been delayed until 1610.

Year (first printed)[edit | edit source]

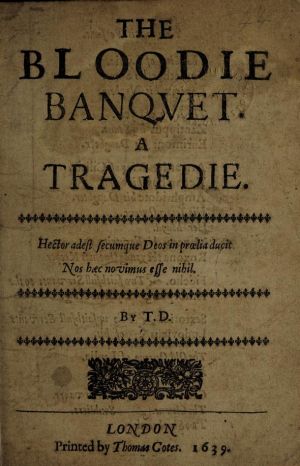

1639. Quarto edition printed by Thomas Cotes.

Reprints (until 1700)[edit | edit source]

None.

Authors (title-page ascription, including reprints)[edit | edit source]

T. D.

Authors proposed (attribution scholarship)[edit | edit source]

Thomas Dekker and Thomas Middleton, plus an unidentified adapter.

The Bloody Banquet consists of 16 scenes, plus an Induction. The division of labour between the play’s two main collaborators and the subsequent adapter was likely as follows:

Dekker: 1.1–3, 2.1–2, 2.4, and 5.1.110sd2–5.1.248sd1 (from the stage direction ‘Thunder and lightning. A blazing star appears’ to the play’s final ‘Exeunt omnes’).

Middleton: 1.4, 2.3, 3.1, 3.3, all of Act 4, and 5.1.1–110sd (from the beginning of the scene to the stage direction indicating that Zenarchus ‘dies’).

Adapter: Induction, 2.5 (this scene might have been added to replace material cut from the Lapyrus plot; see below), possibly 3.2 (as this scene cannot confidently be attributed to either Middleton or Dekker), and other more minor textual alterations.

Genre[edit | edit source]

Tragedy.

Sources[edit | edit source]

William Warner’s Pan His Syrinx (1584; second edition 1597). The playwrights based the play on 4 of the 7 stories featured in Warner’s book.

Based on the surviving passages from the play that were included in the book England’s Parnassus in 1600, it appears that Dekker, Henry Chettle, and John Day’s earlier play Cupid and Psyche (June 1600; now lost) also served as a narrative influence (Wiggins #1247).

Auspices[edit | edit source]

Original company undetermined. Later acquired by the King and Queen’s Young Company (aka ‘Beeston’s Boys’).

External Documentary Evidence[edit | edit source]

Payments[edit | edit source]

No extant records.

Stationers’ Register[edit | edit source]

Not entered.

Title-page ascription(s)[edit | edit source]

The ‘T. D.’ of the 1639 quarto is the only contemporary title page attribution.

It is worth noting, however, that other plays by or partly by Thomas Dekker were similarly published bearing the initials ‘T. D.’, including Dekker and Middleton’s 1 Honest Whore (1604).

The title page of The Bloody Banquet also features a Latin motto (‘Hector adest secumque Deos in prœlia ducit’ [Then Hector appeared, bringing the gods to do battle with him] / ‘Nos hæc novimus esse nihil’ [We know these things to be nothing]); the first line is taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the second from Martial’s Epigrams. Such Latin tags more generally are a recurring feature on the title pages of Dekker’s works, but are not unique to Dekker, and so are most suggestive in combination with other evidence for Dekker’s authorship. Interestingly, however, ‘Nos hæc novimus esse nihil’ is also quoted in the 1602 quarto of Dekker’s Satiromastix (1601), under the heading ‘Ad Detractorem’ (A2r).

Biographical evidence (external)[edit | edit source]

Dekker and Middleton are known to have worked as close collaborators at many other times during their respective careers, so their co-authorship of The Bloody Banquet is not a surprising attribution. Specifically, Dekker and Middleton are recognised as the co-authors of the plays 1 Honest Whore (1604), The Roaring Girl (1611), and The Spanish Gypsy (1623, with William Rowley and John Ford); the lost play Two Shapes (1602, with Michael Drayton, Anthony Munday, and John Webster); the prose works News from Gravesend: Sent to Nobody and The Meeting of Gallants at an Ordinary, or: The Walk in Paul’s (both 1604); and the multi-authored royal pageant The Magnificent Entertainment (1604), so their writing partnership is well established. When prose works and lost plays are included in the count, the number of works produced by the Dekker-Middleton partnership (seven) may well be greater than that produced by the more famous Middleton-Rowley partnership (six). (It should be noted that due to the possibility of Middleton’s part-authorship of Dekker, Ford, and Rowley’s The Witch of Edmonton (1621) the number of Middleton-Rowley collaborations could be as high as seven; however, in this case the Dekker-Middleton number would in turn rise to eight.)

Theatrical provenance (external)[edit | edit source]

The play was listed among 45 plays owned by William Beeston and his company (Beeston’s Boys), performing at the Cockpit, in an order issued by Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke (the Lord Chamberlain) on 10 August 1639, specifying works which other companies should not ‘intermedle wth or Act’ (Munro 2012: 164). If Beeston’s Boys was not the original company – which seems certain given that they were not formed until 1637 (Middleton died in 1627; Dekker died in 1632) – then this suggests ownership of the play must have been transferred to them from elsewhere, before mid-1639.

The known history of Beeston’s Boys and their repertory suggests that they would likely have acquired the play from either the Duke of York’s (later Prince Charles’s) Men, Queen Anne’s Men, or the Children of the Queen’s Revels, all companies with whom Dekker and/or Middleton are known to have worked.

Allusions[edit | edit source]

13 extracts from The Bloody Banquet were included in John Cotgrave’s Wit’s Treasury in 1655, although Cotgrave never named the plays he quoted, nor the author(s) he associated with them.

Print and MS attributions[edit | edit source]

The title page ascription to ‘T. D.’ was repeated in the play-lists of Richard Rogers and William Ley (1656) and Francis Kirkman (1661 and 1671).

W. W. Greg (quoted in Schoenbaum 1961: vi) pointed out that as Kirkman is known to have been a friend of Beeston, he may have acquired information regarding the play’s authorship directly from him; however, as the 1639 quarto was already in print by the time Kirkman compiled his 1661 list, he just as likely copied the initials from that edition’s title page.

Edward Archer’s play-list, appended to his copy of the 1656 quarto edition of Middleton, Rowley, and Thomas Heywood’s The Old Law (1619), attributes the play to one ‘Thomas Barker’, although this is an error Archer makes in place of Dekker’s name elsewhere in the same list, when recording Dekker’s known solo-authored plays Old Fortunatus (1599) and Match Me in London (1621).

Anthony à Wood, in his c.1675–80 catalogue of the contents of Ralph Sheldon’s library, unequivocally attributes the play to Dekker (see Baugh 1918).

(All of this evidence suggests Dekker as the play’s most likely author. Yet nowhere in the external evidence is there any indication of his having worked with a collaborator. However, as shown below, this is indicated by a variety of internal evidence, which has largely been identified and set forth in Lake 1975, Jackson 1979, Jackson 1998, Taylor 2000, and Taylor and Lavagnino 2007a.)

Internal Evidence[edit | edit source]

Palaeographical evidence[edit | edit source]

N/A.

Biographical evidence (internal)[edit | edit source]

Evidence for the presence of an adapter in 2.5 is that this scene is completely unlike anything else Dekker or Middleton produced during their respective careers, most obviously with regard to the opening Chorus. This Chorus seeks to cram a lot of information into just 15 lines, and may be a rushed attempt by the adapter to replace plot content that had been removed by their cuts. In comparison, Dekker preferred to write much longer descriptive choruses (such as the 40-line Chorus that begins Act 2 of Old Fortunatus), whereas Middleton more commonly crafted a distinct personality/character for his narrators (as in Raynulph’s chorus that concludes scene 2.2 of Hengist, King of Kent (1620)), a personality which is not provided in this Bloody Banquet Chorus.

Theatrical provenance (internal)[edit | edit source]

As the play calls for the use of props resembling severed human limbs, this could potentially indicate that the play previously belonged to Queen Anne’s Men during their affiliation with the Red Bull Theatre, as the same kind of prop also appears in Heywood’s The Golden Age, which they also owned, and which was originally performed at the Red Bull in 1611 (i.e. just a year or two after The Bloody Banquet was likely first performed): ‘A banquet brought in, with the limbs of a man in the service’ (Gaines and Ioppolo 2023: iii, 2.2.34.1). However, in the absence of firmer evidence for ownership, this remains speculation.

Internal evidence that The Bloody Banquet underwent a process of later adaptation is characteristic of several other plays acquired by Beeston’s company and included in the 1639 order. Specifically, this internal evidence for adaptation could indicate that ownership of The Bloody Banquet passed from its original company through Queen Henrietta’s Men (formed in 1625), before being acquired by Beeston’s Boys. Indeed, the 1639 Beeston’s Boys order includes 4 other plays known to have been adapted for performance by Queen Henrietta’s Men:

- Heywood’s The Rape of Lucrece (1607-8), revised with the addition of new songs and performed by Queen Henrietta’s Men on 30 July 1628.

- Rowley’s Cupid’s Vagaries (c.1611, now lost), for which Master of the Revels Sir Henry Herbert was paid a licencing fee of £1 by Christopher Beeston on 15 August 1633. Christopher Beeston was responsible for the formation of Queen Henrietta’s Men, so this payment is a probable indicator of ownership by them.

- George Chapman’s Chabot, Admiral of France (c.1612), licensed by Herbert on 29 April 1635, and listed as performed by Queen Henrietta’s Men on the title page of the 1639 quarto (which, like the 1639 Bloody Banquet quarto, was printed by Thomas Cotes).

- John Fletcher’s The Night Walker (c.1615), a version of which was licenced by Herbert for performance by Queen Henrietta’s Men on 11 May 1633.

Christopher Beeston, manager of Queen Henrietta’s Men, was the father of William Beeston, manager of Beeston’s Boys, and both companies performed at the Cockpit, so the internal evidence for adaptation in The Bloody Banquet may well lead us to consider Queen Henrietta’s Men as possible previous owners of the play. Furthermore, of the known companies related to these 4 plays, The Rape of Lucrece was originally a property of Queen Anne’s Men and Cupid’s Vagaries was originally a property of the Duke of York’s Men, both of which fit the known acquisition practices of Beeston’s Boys.

Of the 4 plays known to have been acquired by Beeston’s Boys from Queen Henrietta’s Men, 3 (Cupid’s Vagaries; Chabot, Admiral of France; The Night Walker) are known through both external and internal evidence to have been adapted by James Shirley. Given the possible association with Queen Henrietta’s Men, it is tempting to consider Shirley a candidate for the otherwise unidentified adapter of The Bloody Banquet, although this supposition will require further investigation.

Interestingly, in 1640 two playwrights associated with Beeston, Richard Brome and Thomas Nabbes, separately complained about the abridgement of their texts for performance (Bentley 1971: 236-7). This indicates an apparent preference for shorter plays on the part of Beeston, and Beeston’s willingness to commission cuts to pre-existing texts might explain further why the surviving version of The Bloody Banquet is shorter than any other play by Dekker or Middleton (except, in Middleton’s case, The Nice Valour (1622), although this work was published more than two decades after its original performances, and is itself likely a text that has undergone adaptation).

It is worth noting here that the quarto text’s use of act/scene divisions that are clumsily imposed upon the text after 5.1.110 (creating a false scene break into 5.1 and a non-existent ‘5.2’; see below) suggests that the copy of the play that lies behind the quarto may have had its act/scene divisions imposed onto it sometime after its original performance. Indeed, if the play was originally performed at an outdoor theatre (like the Red Bull) it would not have used act divisions (see Taylor 1993), but these would have been added into the play when it transferred to an indoor theatre (the Cockpit). The problematic split in the middle of 5.1 could be evidence of later act/scene divisions added into the text as part of a textual restructuring undertaken following the larger process of adaptation. Claire Kimball and Charlene V. Smith have pointed out that the encounter between Tymethes and the Young Queen in 4.3 benefits from the application of pitch darkness that would have been made possible by performance in an indoor playhouse (Kimball and Smith 2024: 177-8), in similar vein to a ‘dark scene’ in Webster’s Blackfriars play The Duchess of Malfi (1614); if so, it might indicate that something in the dramaturgy of this scene might also have been altered by the play’s adapter, if the play were transported from an outdoor playhouse to the indoor Cockpit.

Metrical evidence[edit | edit source]

In scenes attributed to Dekker, 6 out of 174 rhymes are feminine (3.4%). In scenes attributed to Middleton, 28 out of 208 are feminine (13.5%). The significant split in the frequency of feminine rhymes between these differently attributed scenes provides strong evidence that they are indeed the product of two different hands. Furthermore, these rates seem appropriately Dekkerian and Middletonian respectively (Taylor 2000: 219).

1.3.8–9 (‘Stop her mouth first. Soldiers must have their sport. / ’Tis dearly earned; they venture their blood for’t’), attributed to Dekker, employs the same ‘sport/for[’]t’ rhyme as is also found in both Dekker’s 2 Honest Whore (1605) at 4.1.311–12 (‘Common? as spotted Leopards, whom for sport / Men hunt, to get the flesh, but care not for’t’) and If This Be Not a Good Play, The Devil Is In It at 2.1.121–3 (‘S’bloud if we tosse not them, hang’s agen: a fort / We ha built without, and mand it, this was the sport’). Additionally the ‘ill[s]/pill[s]’ rhyme of 1.3.5–6 (‘Earth, stretch thy throat: take down this bitter pill, / Loathing the hateful taste of his own ill’) also features in Dekker’s 2 Honest Whore at 5.2.488–9 (‘all your Ills / Are cleare purged from you by his working pills’).

Chronological evidence[edit | edit source]

All act and scene divisions in the surviving version of the play are presented logically in sequence, apart from one false scene division in the Cotes quarto that occurs after what is given as line 5.1.110 in the Oxford Middleton edition. This may be suggestive of two hands working in collaboration in the manuscript that was being consulted by the printer, with the change in author being misinterpreted as a division between 5.1 and an unintended ‘5.2’. 5.1 seems to be the only ‘co-authored’ scene in the play (at least, of the scenes that can be confidently attributed).

The difficulty in attributing 3.2 to either Dekker or Middleton may support evidence of adaptation, when the position of 3.2 between 3.1 and 3.3 is considered. If an adapter had removed material from the Lapyrus plot that fell between 3.1 and 3.3, they would have to have replaced that material with a new scene, so as not to violate the so-called ‘law of re-entry’. Furthermore, as this scene stylistically cannot have been by Middleton, if it were by Dekker it would be his only contribution to the Tymethes plot in the entire play (Taylor and Lavagnino 2007a: 365).

Vocabulary[edit | edit source]

Many of Middleton’s favoured contractions are present in this play and constitute suggestive evidence for his part-authorship. One rare occurrence in the quarto text is Sh’had (1.1.75); this occurs 6 times in the Middleton canon, but is rare elsewhere. I’m is used 13 times, I’d twice, ne’er 18 times, e’en thrice, and y’ 6 times, and ’t contractions appear 34 times. Furthermore, h’as and ’tad each appear once (Jackson 1979: 114–15). The abbreviation ’em, often used by Middleton, is not common in the text of The Bloody Banquet, but does appear in the Middleton-ascribed scenes 1.4, 3.3, and 4.3. T’abuse appears at 5.1.27 and five other times in Middleton (The Widow (1615), 1.1.192; The Witch (1616), 4.2.101 and 5.1.66; Hengist, King of Kent, 4.2.27; and The Nice Valour, 5.3.126), but never in Dekker.

Oaths and interjections[edit | edit source]

A possibly Dekkerian oath, s’nails (meaning ‘by God’s nails), occurs at 2.2.27, but many other dramatists are known to have used this oath, meaning it does not constitute strong evidence for Dekker’s presence on its own (Lake: 238).

At 1.4.127 and 2.3.28, we find the oath mass, one Middleton is known to have been fond of using. At 1.4.149 and 2.3.55 we find s’foote, another Middletonian oath, and at 1.4.176 hum, an exclamation very uncommon outside of Middleton.

Most tellingly in the case of oaths and other expletives, of the 39 expletives known to be more common to Middleton that to any other early modern playwright, 19 appear in The Bloody Banquet; this high rate is only surpassed by one other play, Nathan Field’s Amends for Ladies (1610), although it is worth noting that this play is itself 22% longer than the extant version of The Bloody Banquet (Taylor 2000: 207). The Middletonian expletives that appear in The Bloody Banquet are troth, by this light, i’faith, faith, by my faith, mass, by my troth, by the mass, s’foot, puh, why le/law you now, pish, hist, whist, death, pox on, pox of, prithee, how now, I warrant, hum, and and by this hand.

Of these, Jackson observed that the play’s author made use of puh and why law you now 11 times, and noted that la or law is very common in Jacobean drama, but immediately preceding it with why or following it with you is much less common, and why la[w] you is a very rare formulation, except as an indicator of Middleton’s authorship. Jackson found in 4,000 plays only 5 with both puh and why la[w] you: The Bloody Banquet and 4 established Middleton plays, these being The Puritan (1606), 1 Honest Whore, No Wit, No Help Like a Woman’s (1611), and Wit at Several Weapons (1613). Furthermore, my troth can only be found in 7 plays: The Phoenix (1604), Michaelmas Term (1604), A Trick to Catch the Old One (1605), A Mad World, My Masters (1605), The Puritan, Wit at Several Weapons, and Shakespeare’s Coriolanus (1608), the latter being the only non-Middleton example (1998: 4).

Additionally, a murren on you or a murren on them is an unusual oath formulation in the extant corpus of early modern drama, but it also appears in Middleton’s Hengist, King of Kent at 5.1.263. Similarly, a murren meet ’em appears in A Mad World, My Masters at 2.6.77, and The Revenger’s Tragedy (1606) at 3.6.84 (Holdsworth 1994). Dekker, however, does use how a murrain in The Shoemaker’s Holiday (1599) at 4.2.48 (Taylor and Lavagnino 2007b: 366), although this resembles the Middleton parallels markedly less.

The oath s’light also appears in Middleton’s The Widow and Your Five Gallants (1607).

Linguistic evidence[edit | edit source]

One stand-out piece of evidence regarding Middletonian spellings has been pointed out in Taylor and Lavagnino, namely that ‘trechery’ (4.3.240) and ‘trecher’ (4.3.257) parallel Middleton’s spellings of these words in his 1624 play A Game at Chess (at 4.4.14 and 4.2.8 respectively) (2007a: 367).

At 1.1.45, we find the same kind of alliteration between ‘devil’ and ‘duke[dom]’ as can also be found to occur in The Revenger’s Tragedy. Compare The Bloody Banquet’s ‘The devil! The dukedom, the kingdom, Lydia’ with The Revenger’s Tragedy’s ‘Ay, to the devil. – To th’ Duke, by my faith’ (2.1.202).

Stage directions[edit | edit source]

In similar fashion to the conclusion of The Bloody Banquet, an ecclesiastically-disguised character (and more specifically, a ‘good’ character) also appears in the final scenes of Dekker’s If This Be Not a Good Play, The Devil Is In It and The Noble Spanish Soldier (1622), and Dekker and Middleton’s 1 Honest Whore. Crucially, this is not a plot detail found in the Warner source material, and so was evidently an invention of the dramatist(s). In this light, its incorporation into the play’s narrative seems remarkably Dekkerian.

The speech prefix ‘Omn.’ (at 1.1.2) is very rare in Middleton, appearing only once each in Hengist, King of Kent, Women Beware Women (1621), and The Nice Valour. However, ‘Omnes’ as a speech prefix is common in Dekker, appearing multiple times in several of his solo-authored plays: Blurt, Master Constable (1601); Satiromastix; 2 Honest Whore; The Whore of Babylon (1606); and If This Be Not a Good Play, The Devil Is In It.

The stage direction that opens 3.3, ‘Enter Roxano leading Tymethes. Mazeres meets them’ (3.3.0sd) bears a telling Middletonian characteristic, specifically the formulation ‘Enter A meeting B’ or Enter A. B meets A’, a style of entry direction that is unique to Middleton. The fact that this entry direction describes ‘Roxano leading Tymethes’ along what Tymethes calls a ‘blind pilgrimage’ (3.3.1) also resembles the opening stage direction of 3.1 of Middleton’s The Witch: ‘Enter Duchess, leading Almachildes blindfold’ (3.1.0sd).

The use of a ‘blazing star’ in the stage direction at 5.1.110sd2 resembles Dekker’s use of such imagery in 2 Honest Whore 4.2.52, but this image appears frequently in the works of Middleton, most famously in The Revenger’s Tragedy.

Another interesting feature that may be indicative of Middletonian dramaturgy is the application of two banqueting scenes (3.3 and 5.1), the latter of which is a more tragic inversion of the former (see Meads: 154–7). Such a symbolic pairing of banqueting scenes is something that dramaturgically interested Middleton (see Green: 190–1).

Verbal parallels[edit | edit source]

A signifier of Dekker’s presence can be found early in the Cotes quarto, when the list of characters is described as a ‘Drammatis Personae’ (A1v) rather than i.e. ‘Names of the Persons’. This is a description common to Dekker’s works or works involving Dekker, and can be found in quartos of Satiromastix, The Whore of Babylon, The Roaring Girl, The Noble Spanish Soldier, The Wonder of a Kingdom (1623), and The Spanish Gypsy (Lake: 239).

There are many verbal parallels in the play’s text that can be linked to other works by Dekker. The ‘venture their blood’ imagery of 1.3.9 recalls The Whore of Babylon 5.6.19 (‘venture our owne bloud’). The connection between the words ‘dear’ and ‘earn’ (‘’Tis dearly earned’, 1.3.9) also appears in If This Be Not a Good Play, The Devil Is In It 2.1.173 (‘hee that dearest earnes his bread’) and 4.4.11 (‘At how deere rate the careles world does earne’). Lapyrus’s line at 1.3.5-6 (‘Earth, stretch thy throat: take down this bitter pill, / Loathing the hateful taste of his own ill’) also recalls the language of Dekker: in The Whore of Babylon 5.4.12-13 we find ‘fifty Canons throats, / Stretcht wide’; ‘take […] this bitter pill’ recalls The Wonder of a Kingdom 2.1.87-8 (‘Even in this bitter pill (for me) so you / Would play but my Phisician, and say, take it’); and ‘loath[ing] […] taste’ recalls Old Fortunatus 4.1.140 (‘thy gifts I loath to tast’). Of this last point of comparison, a juxtaposition between ‘taste’ and ‘hate’ within 4 words also appears in 2 Honest Whore 1.2.159 (‘he taught her first to taste poison; I hate her for her selfe’).

Another interesting point is the speech at 1.3.19-23, with its focus on prayers for soldiers, a concern also expressed by Dekker in his Four Birds of Noah’s Ark (1609).

Similar Middleton parallels in the play include ‘Right oracle!’ (1.4.25), which recalls The Revenger’s Tragedy’s ‘’Tis oracle’ (4.1.89), where in both senses ‘oracle’ means ‘absolute truth’, and ‘Heart of ill fortune!’ (4.1.45), which strikingly resembles ‘Heart, of chance’ (6.4) in A Yorkshire Tragedy (1605).

‘I never knew the force of a desire / Until this minute’ (1.4.42) resembles The Revenger’s Tragedy 2.2.34-5 (‘I never thought their sex had been a wonder / Until this minute’), Wit at Several Weapons 1.1.210 (‘I never beheld comeliness till this minute’), and A Mad World, My Masters 4.5.17-19 (‘I ne’er knew / At which end to begin to affect a woman / Till this bewitching minute’).

‘Favours are grown to custom ’twixt ’em both: / Letters, close banquets, whisperings, private meetings’ (4.1.32) recalls what Taylor calls Middleton’s fondness for ‘catalogues of debauchery’ (Taylor 2001: 209), as in A Trick to Catch the Old One 5.2.172-3 (‘All secret friends and private meetings, / Close-borne letters and bawds’ greetings’).

Image clusters[edit | edit source]

The line ‘As your son and heir at his father’s funeral’ (1.4.2) recalls Middleton’s fondness for jokes surrounding imagery of a father’s death, which are also made use of in The Puritan 1.1 and The Revenger’s Tragedy 4.2.

Middleton is also known to have identified the imagery of a padlock as something distinctly Italian, as at 1.4.29. See, for example, A Mad World, My Masters 1.2.22–3 (‘kept by the Italian under lock and key’) and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside (1613) 4.4.4–5 (‘padlocks, father; the Venetian uses it’).

Holdsworth (1994) has drawn attention to the rareness of the image of a person in wax at 2.1.62–3 (‘my young prodigal first in wax’), but which is similar to imagery found in Michaelmas Term 4.1.45–6 and A Yorkshire Tragedy 1.51–2. Dekker does use a comparable image in Lantern and Candlelight (1608), but unlike in the Middleton parallels does not use the specific phrase ‘in wax’ (Taylor and Lavagnino 2007a: 367).

The reference to a ‘sea-wolf’ (i.e. a pirate) at 2.1.68 connects the play to all three of the Middleton plays that can be dated to 1611, just a year or two after the composition of The Bloody Banquet: piratical imagery appears in The Roaring Girl, The Lady’s Tragedy, and No Wit, No Help Like a Woman’s.

Imagery connecting the ideas of sport and soldiers (‘Soldiers must have their sport’, 1.3.8) also appears in Dekker’s The Whore of Babylon 4.3.26 (‘tis the souldiers sport’) and 2 Honest Whore 4.1.286–8 (‘Soldiers fight for them […] Thus (for sport sake)’).

The Tyrant’s use of a metaphor about bees at 1.1.26–7 (‘so unload victory’s honey thighs / To let drones feed’) recalls a similar bee-based metaphor used by a villainous character in Dekker’s If This Be Not a Good Play, The Devil Is In It (1.3.162–8).

Another potential Dekkerian image is the combination of widows and orphans as an emotional image, as can be found at 2.1.5 (‘devour a widow and three orphans’), and which is also used by Dekker in The Raven’s Almanac (1609).

In Dekker, Chettle, and William Haughton’s Patient Grissel (1599), Dekker writes a passage in which Grissel is prevented from breastfeeding her two new-born babies (4.1.123–4), which may be recalled in the description of the Old Queen and her famished infants (2.2.9–10).

Finally, the use of wolf imagery in a discussion about strength versus weakness (2.1.74–6) can also be found in Dekker’s Match Me in London at 4.1.58–66.

Critical Debate[edit | edit source]

E. H. C. Oliphant was the first to propose Dekker and Middleton as co-authors of the play, in a Times Literary Supplement article of 1925, and his argument was subsequently endorsed by Gerald J. Eberle in 1948 (725). Oliphant’s analysis was not widely accepted at first, however, despite the fact that, to quote Taylor, Oliphant ‘was the key figure in redefining the Middleton canon in the twentieth century, and almost all of his attributions have been accepted and confirmed by subsequent scholars’ (Taylor 2000: 198). Indeed, in the 1950s Samuel Schoenbaum dismissed Oliphant as having ‘failed to make a convincing case’ regarding the play’s authorship (1955: 226), and Gerald Eades Bentley was even more scornful, stating that ‘The case for Dekker and Middleton is based mostly on parallels and repeated words and phrases – the flimsiest kind of “evidence”’ (1956: iii, 282–3). David J. Lake (1975: 239–41) and MacDonald P. Jackson (1979: 113–16), however, did take the Dekker-Middleton attribution more seriously, and although at the time they considered it far from proven – to quote Jackson’s later words on the matter, at the time they were both ‘non-committal’ (1998: 4) – most scholars now accept The Bloody Banquet to be a collaborative work by Dekker and Middleton; Jackson later substantially revised his opinion, stating that ‘It is clear to me now that those links are so strong as to constitute virtual proof that Oliphant was right’ (1998: 4). In 2007 the play was included as part of the Oxford Middleton, in a text edited by Taylor and Julia Gasper (2007b: 637-69), thus enshrining the play in print as part of the Middleton canon for the very first time; the play had previously been excluded from the Middleton collected works of Alexander Dyce (1840) and A. H. Bullen (1885–7), both of which were published long before Oliphant’s analysis.

Other possible alternative authors have been proposed over the years, although each has seen far less scholarly acceptance. One alternative candidate, promoted by Frederick Gard Fleay, was Thomas Drue (or Drew), the only other known playwright from the time to have the initials ‘T. D.’ (1891: i, 162). However, both Lake and Jackson ruled Drue out in their stylistic analyses of The Bloody Banquet (Lake: 233–4; Jackson 1979: 113–16). Drue is the author of only one other acknowledged play that survives to this day, The Duchess of Suffolk (1624), so an attribution of The Bloody Banquet to Drue could be argued to bring with it little critical enlightenment.

Additionally, David Erskine Baker suggested Robert Davenport as the play’s author on the basis that The Bloody Banquet is listed after several Davenport plays in Herbert‘s list, the argument thus being that the ‘T. D.’ on the 1639 title page was a mistake for ‘R. D.’ (1812: 61). However, this argument is no more persuasive than someone in favour of Middleton’s authorship saying, conversely, that ‘T. D.’ is a mistake for ‘T. M.’ The Davenport theory was nevertheless later revived by James G. McManaway, although he largely based this argument on the fact that the ‘Hector adest secumque Deos in prœlia ducit’ motto on The Bloody Banquet’s title page also appears on the manuscript of the anonymous play Dick of Devonshire (1626-7), which McManaway (on little evidence) also attributed to Davenport (1946: 34). McManaway claimed to have found ‘considerable internal evidence that [The Bloody Banquet] and Dick of Devonshire are from the same pen, and that the writer was indeed Robert Davenport’ (35), but he did not proceed to provide this supposed evidence. Davenport’s authorship of Dick of Devonshire is no longer supported in present-day scholarship; indeed, Heywood is believed to be a much more likely candidate (see e.g. Long 2014; Greatley-Hirsch, Pangallo, and White 2024).

Critical Commentary[edit | edit source]

The authorship of 3.2 is uncertain. The scene displays Dekker’s fondness for hath over has, and this form of the word occurs twice in this short scene; however, hath was a popular form used by many other dramatists, so is not necessarily a strong indicator of Dekker’s authorship specifically, and could just as easily be the preference of the play’s adapter. In the absence of firmer evidence, the author of 3.2 remains undetermined. However, as with many surviving early modern plays published many years after their original composition and performance, the presence of an adapting hand in The Bloody Banquet seems incredibly likely.

Given its relatively short length, it is generally agreed that the Cotes quarto reproduces an abridged text of the play, something we know was a theatrical practice undertaken by Beeston’s company (see above). Schoenbaum (1961: vii-viii) observed numerous curiosities in the text that are at the very least suggestive of significant cutting and other forms of alteration. These include (I hear indicate cut material using < >):

- A line seemingly lost at Induction.Chorus.11 (‘This Lord Lapyrus entertained and welcomed / By < >, / But chiefly by the fair Eurymone’).

- Further lines possibly removed from 1.1.154–5 (‘Or if for larger bounties < > I was mad’), 4.3.106-8 (‘Had any warning fast’ned on thy senses, / < > / Rash, unadvisèd youth, whom my soul weeps for’), and 5.1.13–16 (although in this case such a cut is not noted in the Oxford Middleton text).

- An incomplete line at 1.4.29 (‘Italian padlocks, < >’).

- Sextorio and Lodovicus being named as such in the ‘Drammatis Personae’ and in 1.1, but then becoming ‘Sertorio’ and ‘Lodovico’ in Acts 4 and 5.

- Armatrites being named as such in speech prefixes throughout 1.1, but becoming simply ‘Tyrant’ from then on.

- The Young Queen claiming ‘I speak strange words against my fantasy’ at 1.4.66, despite having done no such thing.

- The Old King of Lydia saying ‘On thee, Lapyrus, and thy treacheries, fall / The heavy burden of an old man’s curse’ at 1.1.69–70, and calling him an ‘Inhuman monster!’ at 2.4.3, but then easily forgiving him just 9 lines later (‘Set all our hands to help him. – Come, good man’, 2.4.12) with no clear indication as to why. This differs substantially from the Warner source material.

- The King of Lycia, Zantippus, and Eurymone being afforded noteworthy status by being listed in the play’s ‘Drammatis Personae’, but only appearing in the dumb show of the Induction.

Most striking, however, is a change in the play’s narratives after Act 2. As Schoenbaum noted, in Acts 1 and 2 the playwrights establish the story of the Young Queen, Tymethes, and the Tyrant in 3 scenes, while 5 are devoted to the tale of the Old Queen, Lapyrus, and the King. After this, the latter story is not picked up again until the final scene, when they appear disguised as pilgrims. It is never explained why they are dressed in such a fashion or from where they acquired such garments, suggesting a significant amount of subplot material may have been removed from the play by an adapting hand. Acts 2, 3, and 5 are also markedly short in comparison with Acts 1 and 4, which may be further evidence of substantial cutting; if the respective lengths of Acts 1 and 4 were replicated throughout the play, The Bloody Banquet would be of an average length for drama of the period, so the play’s brevity is seemingly a consequence of the unusual shortness of Acts 2, 3, and 5. It thus appears that the adapter considered material from the Lapyrus plot the most worthy of being dispensed with.

Interestingly, given the amount of scenes focusing on the Lapyrus plot in Act 1 compared with amount of scenes dedicated to the Tymethes plot in the same Act, it is possible that the importance of the plots has been reversed in the extant version of the play. Whereas now the Lapyrus plot appears to be something of a subplot, in the original version the story of Lapyrus might have been the majority focus, with the Tymethes plot taking subplot status. While the play’s title, The Bloody Banquet, clearly relates to the Tymethes plot, this was not necessarily the title of the play under which it was originally performed in c.1609 (and in any case, plays did sometimes take their titles from their subplot).

Further Thoughts[edit | edit source]

Works Cited[edit | edit source]

Barroll, Leeds (1991), Politics, Plague, and Shakespeare’s Theater: The Stuart Years (New York: Cornell University Press).

Baker, David Erskine (1812), Biographia Dramatica, or, A Companion to the Playhouse (Dublin: T. Henshall).

Baugh, Albert C. (1918), ‘A Seventeenth Century Play-List’, Modern Language Review (13), 401–11.

Bentley, Gerald Eades (1956), The Jacobean and Caroline Stage, vol. iii (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Bentley, Gerald Eades (1971), The Profession of Dramatist in Shakespeare’s Time (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Bowers, Fredson, ed. (1953–61), The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker, 4 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). All quotations from the works of Dekker are from this edition.

Eberle, Gerald J. (1948), ‘Dekker’s Part in The Family of Love’, in James G. McManaway, Giles E. Dawson, and Edwin E. Willoughby (eds), Joseph Quincy Adams Memorial Studies (Washington: Folger Shakespeare Library), 723–38.

Fleay, Frederick Gard (1891), A Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama 1559–1642, vol. i (London: Reeves and Turner).

Gaines, Barry, and Grace Ioppolo, eds (2023), The Collected Works of Thomas Heywood, vol. iii (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Greatley-Hirsch, Brett, Matteo Pangallo, and Rachel White (2024), ‘“Text up his name”: The Authorship of the Manuscript Play Dick of Devonshire’, Studies in Philology (121), 163-87.

Green, William David (2020), ‘“Such Violent Hands”: The Theme of Cannibalism and the Implications of Authorship in the 1623 Text of Titus Andronicus’, Exchanges (7), 182–99.

Holdsworth, R. V. (1994), ‘A Middleton Oath in A Yorkshire Tragedy and The Bloody Banquet’, Notes and Queries (239), 70.

Jackson, MacDonald P. (1998), ‘Editing, Attribution Studies, and “Literature Online”: A New Resource for Research in Renaissance Drama’, Research Opportunities in Renaissance Drama (37), 1–15.

Jackson, MacDonald P. (1979), Studies in Attribution: Middleton and Shakespeare (Salzburg: Universität Salzberg.

Kimball, Claire, and Charlene V. Smith (2024), ‘The Bloody Banquet in Performance’, in William David Green, Anna L. Hegland, and Sam Jermy, eds, The Theatrical Legacy of Thomas Middleton, 1624–2024 (London: Routledge), 169-84.

Lake, David J. (1975), The Canon of Thomas Middleton’s Plays: Internal Evidence for the Major Problems of Authorship (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Long, William B. (2014), ‘Playhouse Shadows: The Manuscript Behind Dick of Devonshire’, Early Theatre (17), 146–68.

McManaway, James G. (1946), ‘Latin Title Page Mottoes as a Clue to Dramatic Authorship’, The Library (26), 28–36.

Meads, Chris (2001), Banquets Set Forth: Banqueting in English Renaissance Drama (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

Munro, Lucy (2012), ‘Middleton and Caroline Theatre’, in Gary Taylor and Trish Thomas Henley, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Thomas Middleton (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 164–80.

Oliphant, E. H. C. (1925), ‘The Bloodie Banquet, A Dekker-Middleton Play’, Times Literary Supplement (17 December), 882.

Schoenbaum, Samuel, ed. (1961), The Bloody Banquet (Oxford: Malone Society Reprints).

Schoenbaum, Samuel (1955), Middleton’s Tragedies: A Critical Study (New York: Columbia University Press).

Taylor, Gary (2001), ‘Gender, Hunger, Horror: The History and Significance of The Bloody Banquet’, Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies (1), 1–45.

Taylor, Gary (1993), ‘The Structure of Performance: Act-Intervals in the London Theatres, 1576-1642’, in John Jowett and Gary Taylor, eds, Shakespeare Reshaped, 1606-1623 (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 3–50.

Taylor, Gary (2000), ‘Thomas Middleton, Thomas Dekker, and The Bloody Banquet’, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America (94), 197–233.

Taylor, Gary, and John Lavagnino, eds (2007a), Thomas Middleton and Early Modern Textual Culture: A Companion to the Collected Works (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Taylor, Gary, and John Lavagnino, eds (2007b), Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works (Oxford: Clarendon Press). All quotations from The Bloody Banquet and other works by Middleton are from this edition.

Page created and maintained by William David Green; updated on 24 March 2023.